Elizabeth Warren has a plan to wreck the economy

It's not a normal anti-gouging bill. It's much worse.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) last week introduced a bill “to make price gouging unlawful, to expand the ability of the Federal Trade Commission to seek permanent injunctions and equitable relief, and for other purposes.” In other words, price controls.

If passed and enforced vigorously it would wreck the economy.

A fair number of people instinctively recoil at price control measures as desperate flailing by incompetent politicians. They can draw the supply and demand chart, and describe the deadweight losses of shortages, and they aren’t interested in further discussion. While I have sympathy for this perspective, it’s important to drill down further in this case.

This isn’t like an ordinary anti-gouging bill; it’s far worse. Our current situation is different from the situations where the gouging debate usually applies, and price controls would be unusually bad.

The bill is unlikely to pass, and there are indications that even many Democrats aren’t taking it seriously. But these “messaging” bills often make real problem solving harder.

You can’t solve macro problems with micro solutions

Typically, when you think of the “gouging” debate, you imagine some narrow market over some short period of time—like the market for items that require refrigeration in the wake of a massive power outage caused by a huge storm.

And you can have a familiar debate; with market prices, you might induce a little bit of extra supply, and allocate supplies to the people who are willing to pay the most at the margin, which can be seen as a proxy for need (I fall on this side of the debate). With price controls, you can help the finances of consumers hit by the storm—but you prevent producers from getting compensation for working in extraordinary circumstances.

A lot of people are falling along the lines of the old, familiar debate. In fact, some people, like Alex Harman, an antitrust specialist at the left-leaning group Public Citizen, explicitly drew the analogy between the Warren bill and these typical price gouging debates. “The legislation in question is not some new wild concept. There is price gouging legislation in 3/4ths of the states and many of them use exactly this language of ‘unconscionably excessive.’ This is not new and is widely accepted as necessary in times of emergency,” he wrote on Twitter.

But these state-level price gouging bills are inspired by narrow circumstances like natural disasters, and demand in those situations isn't actually analogous to demand in our current economy. I described a very contained, micro issue. It happens in a specific place and time and market. What we have here is a broad and longer-lasting macro situation covering the whole economy.

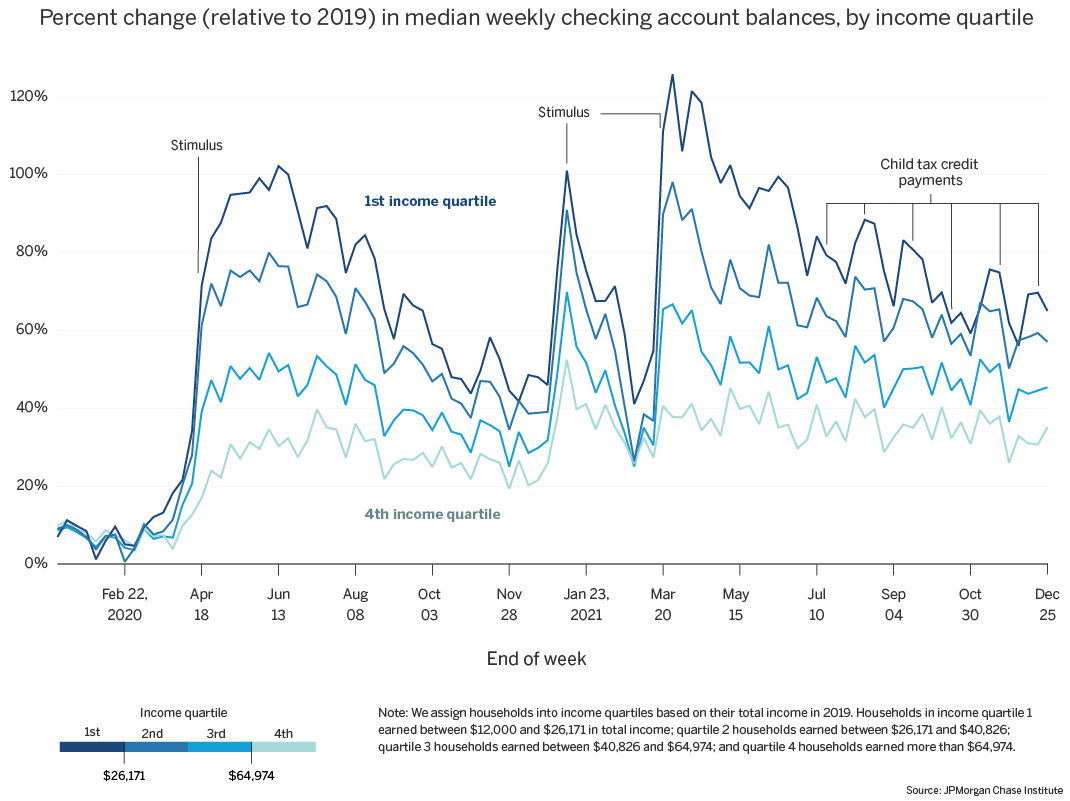

The situation we have on hand—I won’t call it a problem, but I won’t call it a good thing either—is that Americans have lots of dollars on hand, and are ready to spend them. The above chart, showing high checking account balances since the beginning of the pandemic and the CARES Act, comes from the JP Morgan Chase Institute's Household Pulse survey. As we’ve shown before, they have enough money to spend more than they did in the past, and in fact, more than they would have been able to if pre-COVID-19 trends had continued unabated. To consumers, it’s a great time to spend tons of money.

This situation has to resolve itself somehow. And it is likely to resolve in the way it has thus far: consumers compete for scarce goods and services, prices get bid up, and their balance sheets run down, until eventually, people’s willingness and ability to spend is once again aligned with price levels.

This is a macro situation. Dollars are rushing down out of bank accounts, and they want to go places and acquire stuff. Trying to address this situation by playing “whack-a-mole” in a series of individual markets doesn’t work.

Imagine, for example, that you live in a basement apartment and there’s a bathroom flooding on the upper level and water is coming down through your ceiling. And imagine your plan to fix it is to simply stop up the specific spots where water is coming down most. You block those leaks, but then the water begins relentlessly rushing down in new places.

That’s why you can’t use micro solutions to macro problems. Because even if you successfully control prices in one area, that simply gives American households even more money to spend elsewhere. Then you get more “unconscionably excessive” prices, and you have to go control prices in those other areas too.

What would happen if we took it seriously?

I think there are plenty of reasons not to take this bill seriously. We’ll get to those. But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, we went through with this sort of legislation more broadly. How does a situation with plentiful money, scarce goods and price controls end up resolving itself?

One way, I’ll call “scalper’s paradise.” Official prices are low, but usually unavailable, or at least, unavailable on any reasonable timeline. But there’s a large market of scalping and reselling by firms and people small enough to avoid scrutiny. You have plentiful money, but you often have to pay the scalper’s price—the true market price—to get the good.

But say you crack down completely on scalpers too. Then you get “unspendable money.” If the price controls are truly binding, and successfully enforced, you reach a peculiar situation where you have plenty of the official currency, and, in theory, plenty of purchasing power at the official prices. But you have little ability to find goods at those official prices. The official prices are cheap, so any time something is available at the official price it gets snapped up instantly. Measured against the official prices, your wealth is quite high, but you have little ability to use that wealth.

In these sorts of economies, the ability to buy things at the official “fair” price is extremely valuable, since without that ability you end up paying a scalper, or you end up with unspendable money. Often, a network of favor trading develops among people and enterprises; rather than trading goods and services in a market, at market prices, they barter for the ability to buy things at official prices.

If this all sounds a little bit Soviet to you, you’re not wrong. Gregory Grossman noted that market forces tended to reassert themselves in the USSR in creative ways, often in contravention of official command economy rules. He called this the Second Economy.

Is any of this likely to take place? No. The votes aren’t there. This bill isn’t even likely to get “normal” moderate Democrats aboard, much less crucial swing votes like Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ). And you can forget about Republicans entirely.

But I think it’s worth a conversation about who we “take seriously” in politics.

Who’s the real rube?

There’s an interesting passage from the Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell, an opinion columnist critical of the bill.

I’ve been scolded before, including by White House senior aides, for making a fuss about Democrats’ demagoguery on this issue. So what if Biden and Democratic lawmakers want to grandstand about corporate greed? Who cares whether Biden asks for another gratuitous investigation into whether “illegal” conduct is driving up gas prices? This kind of populist anti-corporate rhetoric polls well, they say. It does no harm. It’s just cheap talk, so Democrats can show they’re Doing Something about inflation.

In Rampell’s telling (or at least, Rampell’s paraphrase of Democratic aides) Democrats aren’t very sincere on this issue, and simply are using it to score points with anti-corporate voters. This is a simple and often useful way to think about some issues. Sometimes politicians are simply inventing fake beliefs to get votes, and that’s the whole story.

But a great number of Democratic partisans—even in demographics that are ostensibly highly educated—are under the impression that Senator Warren is the serious, “wonkish” individual—the grown-up who proposes smart plans. The White House aides Rampell talked to don’t see it that way.

Whenever a stated agenda and a hidden agenda differ from each other, it’s hard to tell what’s real and what isn’t. At the New York Times, Paul Krugman seems to think the price controls aren’t real. “Even the Warren bill, while it would require large firms to offer explanations for price hikes, is far short of a true price control measure,” he wrote on Twitter. Krugman seems to retreat to the idea that the real position is only that corporate concentration and gouging have some role in inflation.

Perhaps Krugman didn’t know the contents of the bill. His comments suggest he may have judged by the headline of the Bloomberg story he saw without reading the body of the article or the bill itself. But it seems he comes from a perspective where price controls obviously aren’t a part of the serious Democratic wonk’s agenda.

Nonetheless, the bill, nominally from the most serious Democratic wonk, makes “unconscionable” price increases illegal, it makes some attempt to define them, and it enumerates specific fines for noncompliance. It is a price control bill.

What’s going on here? When politicians start advocating a position—sincerely or otherwise—you attract people who take those beliefs seriously, and politicians may even come to depend on them for votes. Over the long run, it may eventually become unclear what’s the “real” position.

The way I’d resolve this is to say that positions are always “real” to some advocates, and “rhetorical concessions” to other people. What ultimately matters is what bills pass. And this one won’t.

But even positions that don’t become law can still have an effect on politics and policy. I think Rampell has a good handle on the issue: “Such allegedly cheap talk has become very expensive…it has distracted Democrats from taking actions that could help, because this ‘greedflation’ narrative has persuaded both policymakers and the public to misdiagnose the problem’s causes.” Warren’s bill isn’t going to pass, but leaders like Warren—with her Emperor’s New Clothes reputation for wonkishness—are distracting many Democrats from taking action on excessive aggregate demand.